Table of Contents

- Who does the FATF’s Recommendation 16 “travel rule” apply to?

- Which countries have to comply with the FATF R.16?

- FATF’s 39 member countries

- The 9 FATF-Style Regional Bodies (FSRB)

- What happens if countries don’t comply?

- What happens if VASP exchanges don’t comply?

- How are VASPs affected by Recommendation 16?

- Why do VASPs and countries struggle to work together on an R.16 solution?

UPDATE: Read the latest on the FATF’s new 12-Month Review set for June 2021

The Financial Action Task Force (FATF)’s June 2019 plenary heralded disruptive changes to the cryptocurrency landscape and specifically its virtual asset service providers (VASPs).

The FATF Recommendation 16 for Wire Transfers requires VASPs to share certain data with each other, as first detailed on in February 2019’s Interpretive Note to Recommendation 15, Paragraph 7(b)-R.16.

FATF jurisdictions had to show that they’ve come with up sufficient solutions by June 2020. Yet, of the FATF’s 200 countries, only 35 jurisdictions reported their transposition of Travel Rule legislation, due to implementation challenges and the COVID-19 pandemic.

As a result, the FATF has issued a new 12-month review set to conclude in June 2021, that will allow the virtual asset industry and FATF to deal with with new challenges such as the “Sunrise”issue of jurisdictional rollout as well as establishing interoperability between technical solutions.

In this article, let’s look at the different variables, parties involved and territorial setup of the FATF.

It is important to note that while the FATF exercises a strict Anti-Money-Laundering (AML) and Combating Funding of Terrorism (CFT) policy influence over the 200+ countries under its jurisdiction, none of its 40 Recommendations (guidances intended to facilitate effective global AML/CFT) are legally binding.

The FATF Recommendations (also known as the FATF Standards) act as guidelines that member countries are expected to refer to and then expand further domestically. The second key distinction to make relates directly to Recommendation 16.

Who does Recommendation R16 apply to?

Recommendation 16’s “Travel Rule” clause:

Countries should ensure that

…beneficiary VASPs obtain and hold required originator information and required and accurate beneficiary information on virtual asset transfers, and make it available on request to appropriate authorities.

…originating VASPs obtain and hold required and accurate originator information and required beneficiary information on virtual asset transfers, submit the above information to beneficiary VASPs and counterparts (if any), and make it available on request to appropriate authorities.

Note that in the guidance, it is clear that the onus falls squarely on countries to ensure that they get their local VASP industry in order.

Therefore, you could say that Recommendation 16’s crypto travel rule clause impacts member countries directly, and virtual asset service providers (VASPs) indirectly.

How are VASPs defined by the FATF?

In October 2018, the FATF adopted changes to its Recommendations to explicitly clarify that they apply to financial activities involving virtual assets, and also added two new definitions in the Glossary, to clearly define “virtual asset” (VA) and “virtual asset service provider” (VASP).

A Virtual Asset Service Provider (VASP) is defined by the FATF as follows:

Any natural/legal person who is not covered elsewhere under the Recommendations, and as a business conducts one or more of the following activities or operations for or on behalf of another natural or legal person:

i. exchange between virtual assets and fiat currencies;

ii. exchange between one or more forms of virtual assets;

iii. transfer1 of virtual assets;

iv. safekeeping and/or administration of virtual assets or instruments enabling control over virtual assets; and

v. participation in and provision of financial services related to an issuer’s offer and/or sale of a virtual asset.

It can be summarized as below:

[1.] In this context of virtual assets, transfer means to conduct a transaction on behalf of another natural or legal person that moves a virtual asset from one virtual asset address or account to another.

In layman’s terms, A VASP constitutes any individual or entity that provides one or more of the following services to others as a business:

- Fiat and virtual asset exchange;

- An exchange between virtual assets;

- Transfer of virtual assets

- Safekeeping of virtual assets; or

- Activities related to issuing or underwriting virtual assets

VASPs are most often centralized digital exchanges, but they can also include any financial institution (FI ) such as banks or investment houses that have any dealings with cryptocurrencies.

Which Countries Need to Comply with Recommendation 16?

The Financial Action Task Force is a very influential organization, founded by the G7 in 1989 to combat money laundering and later terrorism funding. It enjoys the support of both the G20 and the United Nations and works closely with these organizations to establish a blanket regulatory AML/CFT policy worldwide.

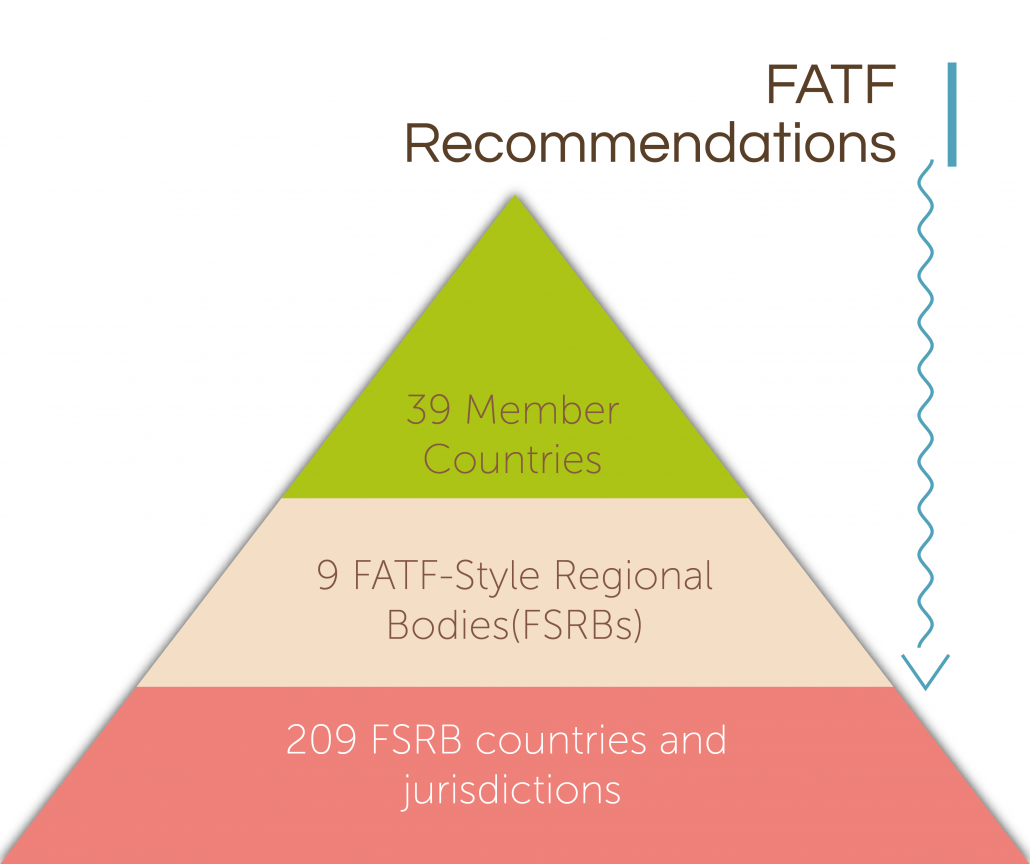

To ensure that its recommendations are successfully implemented around the world, the FATF works closely with both its 39 members (37 countries and 2 special jurisdictions) as well as a global network of nine FATF-Style Regional Bodies (FSRBs) that influence the AML policies of nearly all the countries in the world.

The FATF’s 9 FSRBs are critical to the success of the FATF Recommendations, as they extend the organization’s reach, add their own input and expertise, and ensure the standards are effectively disseminated and implemented in each of the over 200 jurisdictions worldwide that have committed to the guidances.

Let’s break down the different countries and regional organizations impacted by the FATF’s Recommendations as follows:

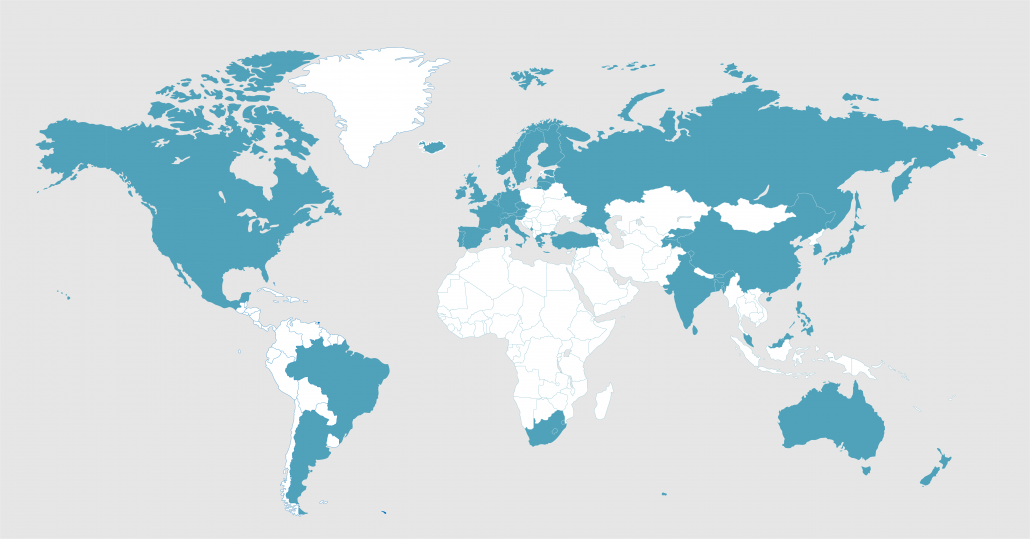

The FATF’s 39 Member Countries and Special Jurisdictions

The countries below are the FATF’s 39 official members, who are expected to comply with its Recommendations. They are also members of the FSRBs in their regions, where they usually take a leading role to assist non-member countries with implementing the Recommendations. In addition, Indonesia is currently an observing member.

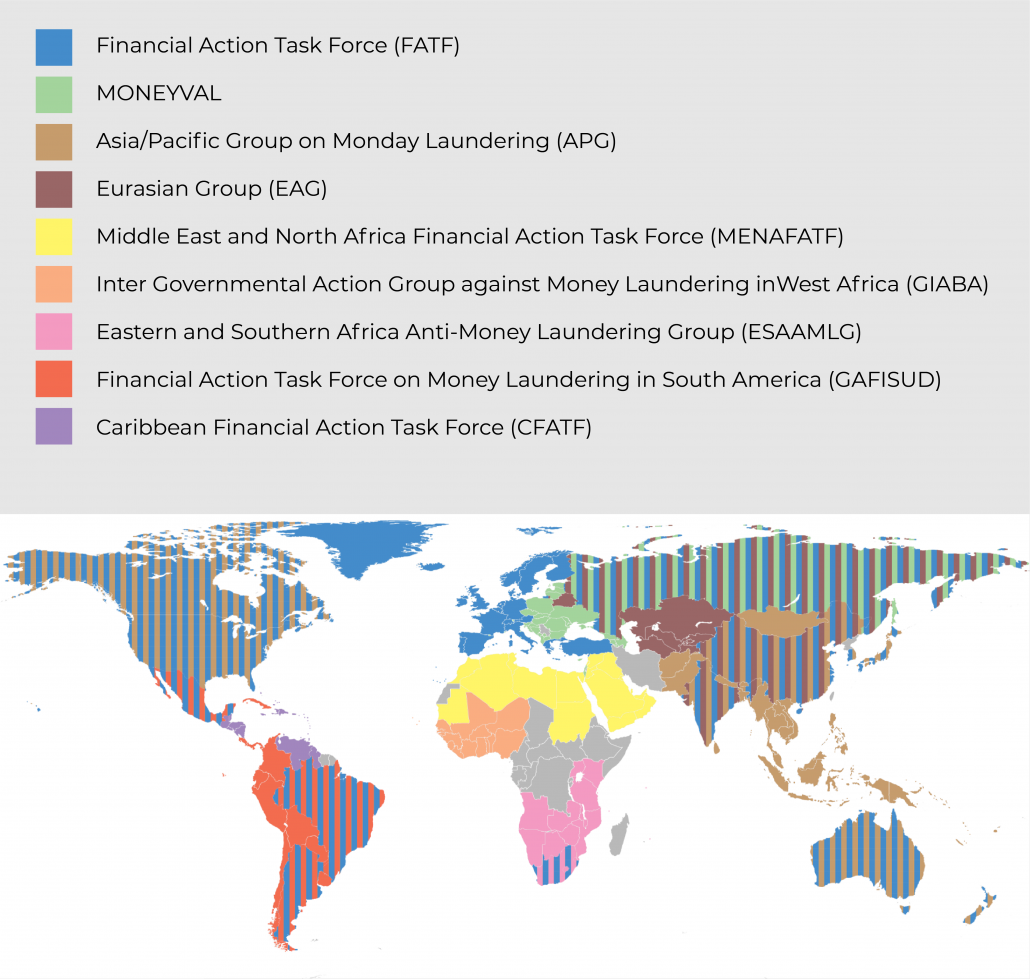

The Nine FATF-Style Regional Bodies (FSRBs)

The 9 FATF FSRBs are spread across the globe, each tackling a specific region to help its respective countries understand and implement FATF’s requirements. At present, there are over 200 countries and jurisdictions that belong to the FATF-Style Regional Bodies. Territories are eager to join the FSRBs in their area to avoid being added to the FATF’s High-Risk Country Monitoring graylist, or worse, the blacklist, which currently features Iran and North Korea.

| Acronym | Full Name | City | Country |

| APG | Asia/Pacific Group on Money Laundering | Sydney | Australia |

| CFATF | Caribbean Financial Action Task Force | Port of Spain | Trinidad & Tobago |

| EAG | Eurasian Group | Moscow | Russia |

| ESAAMLG | Eastern & Southern Africa Anti-Money Laundering Group | Dar Es Salaam | Tanzania |

| GABAC | Central Africa Anti-Money Laundering Group | Libreville | Gabon |

| GAFILAT | Latin America Anti-Money Laundering Group | Buenos Aires | Argentina |

| GIABA | West Africa Money Laundering Group | Dakar | Senegal |

| MENAFATF | Middle East and North Africa Financial Action Task Force | Manama | Bahrain |

| MONEYVAL | Council of Europe Anti-Money Laundering Group | Strasbourg | France |

What does FATF expect of countries and VASP regarding virtual assets?

The FATF expects countries to do the following:

- “implement the same preventive measures as financial institutions, including customer due diligence, record keeping and reporting of suspicious transactions.”

- Obtain, hold and securely transmit originator and beneficiary information during transfers

For VASPs, they need to:

- Understand the money laundering and terrorist financing risks the sector faces

- License or register virtual asset service providers

- Supervise the sector, in the same way it supervises other financial institutions

The FATF does not expect VASPs to make their users’ identities public, but to only share it with transmittal counterparts.

What happens if countries don’t comply with the FATF?

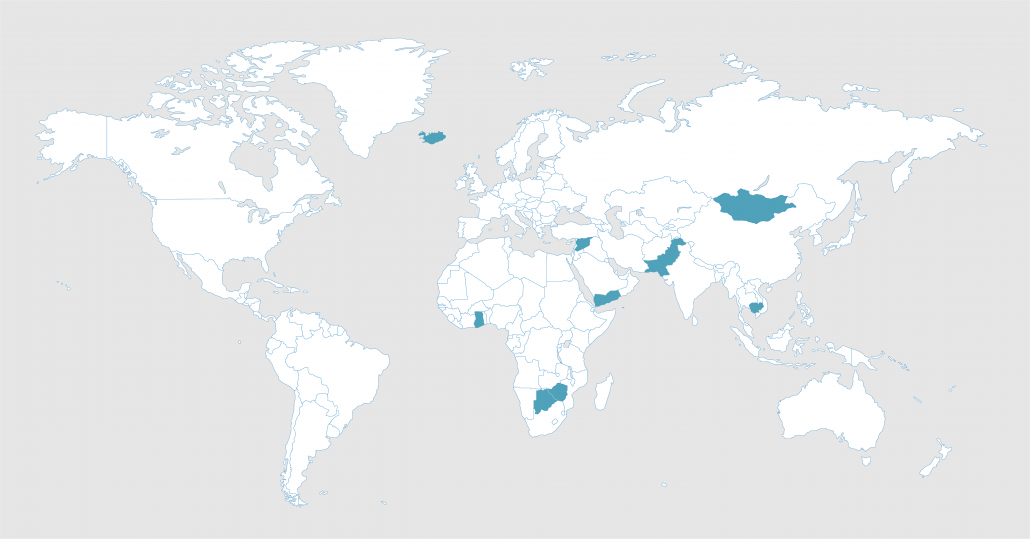

The current FATF graylist

When a country repeatedly fails to implement satisfactory AML/CFT systems and is considered to be a global AML liability, the FATF has the option to add it to a High-Risk Monitoring List, also known as the FATF graylist. These countries are monitored by the FATF, who work closely with them to resolve their money laundering vulnerabilities.

While there were as many as 68 countries on FATF’s “graylist” in 2018, there are currently in May 2020 only 16 left:

| Albania Bahamas Barbados Botswana Cambodia Ghana Iceland Jamaica Mauritius | Mongolia Myanmar Nicaragua Pakistan Panama Syria Uganda Yemen Zimbabwe |

The FATF blacklist

Monitored countries that continue to insufficiently improve their AML defenses risk getting added to the feared Non-Compliant Countries and Territories (NCCT), the FATF’s “blacklist” that leads to global economic and political isolation. Currently, only Iran and North Korea occupy the list.

What happens if VASPs don’t comply with Recommendation 16?

As previously explained, VASPs will not directly bear the FATF’s wrath if Recommendation 16 isn’t implemented. Instead, the FATF targets the 200+ countries listed above and helps them comply by interacting with the 9 FSRBs. After engaging with the regional FATF organizations, countries should know what is expected of them and can start to draft suitable legislature to enforce FATF’s recommendations.

While the FATF Recommendations are occasionally vague in their wording, their intentions rarely are. Countries will have to comply or risk the consequences.

This could result in a forced shutdown or outright ban of FATF-transgressing exchanges by 2021. So it’s clear that Recommendation 16 indeed offers an existential threat to all VASPs.

What is required of VASPS to comply with Recommendation 16?

Countries are expected to ensure that VASPs operating in their jurisdictions comply with the FATF’s Recommendations, where (according to paragraph 113 of the Draft Guidance for a Risk-based Approach to Virtual Assets and VASPs), where transactions in excess of 1000 USD or Euro in either virtual or fiat currency are involved.

According to the FATF Interpretive Note to Recommendation 15, beneficiary and originator VASPs will have to share the following information:

- Originator’s name and account number

- Originator’s physical address, or national identity number, or customer identification number, or place and date of birth

- Beneficiary’s name and account number

Since virtual assets and VASPs use electronic technology to facilitate transactions that transcend traditional, real-world borders, the FATF has advised countries to treat all virtual asset (VA) transfers as cross-border transfers, rather than domestic wire transfers, in accordance with the Interpretative Note to Recommendation 16 (INR. 16).

Both countries and VASPs will have to come up with a satisfactory response to Recommendation 16 before June 2021, and implement suitable applications to ensure compliance or face walking the plank towards the FATF blacklist.

This threat ensures that countries will transfer the FATF’s regulatory pressure directly on to VASPs under their jurisdiction, “encouraging” VASPs to come up with industry-led solutions. VASPs that take ineffective to no action run the risk that they force the hand of their country or regional authority to then create and foist its own compliance solution on them. Due to the complex nature of cryptocurrencies and countries’ lack of technical understanding and resources, a country-created Recommendation 16 solution might be technically and financially very difficult to implement.

What stops VASPs and Countries from finding a Recommendation 16 solution?

There are several issues that stop VASPs and countries around the world from collaborating to create and onboard a suitable solution to Recommendation 16, such as the following:

- Cryptocurrency’s underlying blockchain technology doesn’t have an intermediary layer that can collect the necessary personally identifiable information (PII). One must be created.

- Any protocol that is adopted by the VASP industry will need to be a technical solution that is scalable, cost-effective, applicable to all virtual assets and quick to install with minimal disruption.

- VASPs are usually notoriously competitive with each other, libertarian by nature and hate government interference. The “travel rule” forces all VASPs to work not only with each other but also with the very authorities that they might despise or have rocky relations with.

- Massive cultural, linguistic and regional barriers will have to be overcome before a global solution for all VASPs is agreed on.

Written by Werner Vermaak

About CoolBitX and Sygna Bridge

CoolBitX’s Sygna Bridge is a first-to-market travel rule solution and alliance network that is live and being used by our VASP partners to share compliant originator and beneficiary transmittal information.

Sygna Bridge completed a successful production test report (Big 4 audited) earlier this year, which was presented to the FATF Contact Group in May 2020. Sygna Bridge now also supports the IVMS101 messaging standard.

CoolBitX has signed MoUs with 18 VASPs worldwide and recently joined forces with Elliptic in a combined quest to help crypto companies comply with the FATF Standards.

For enquiries on the FATF Travel Rule and our Sygna Bridge solution for VASPs, please contact us at info@sygna.io.